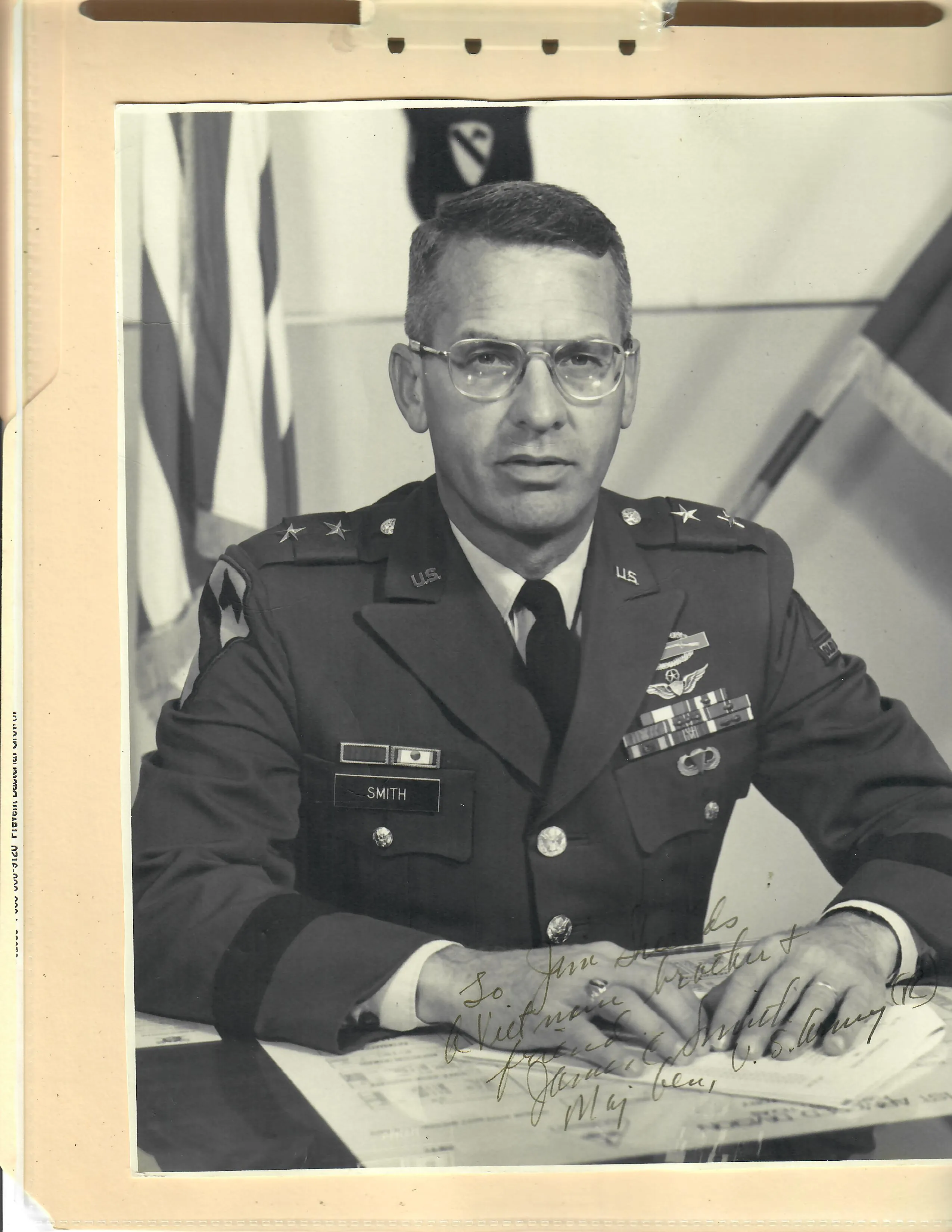

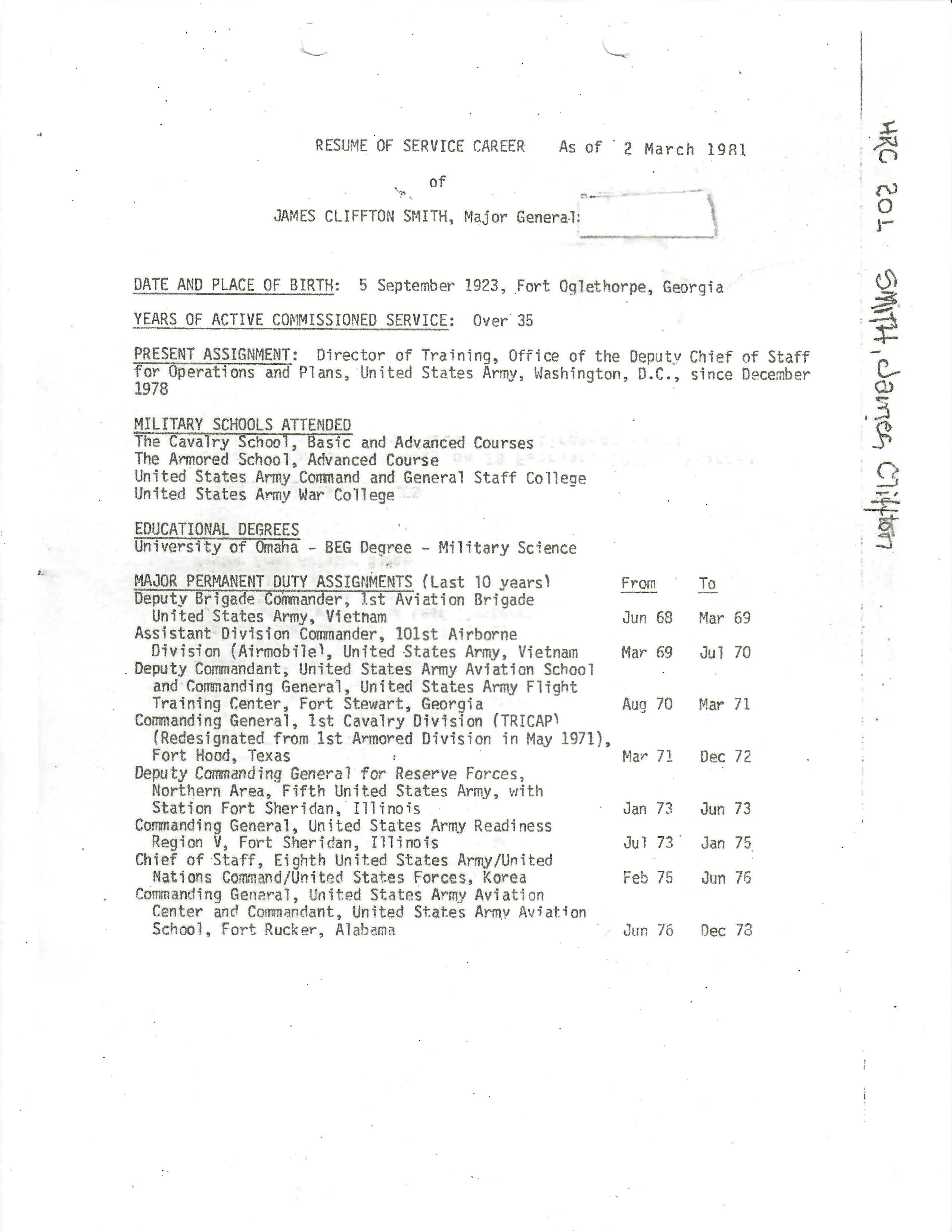

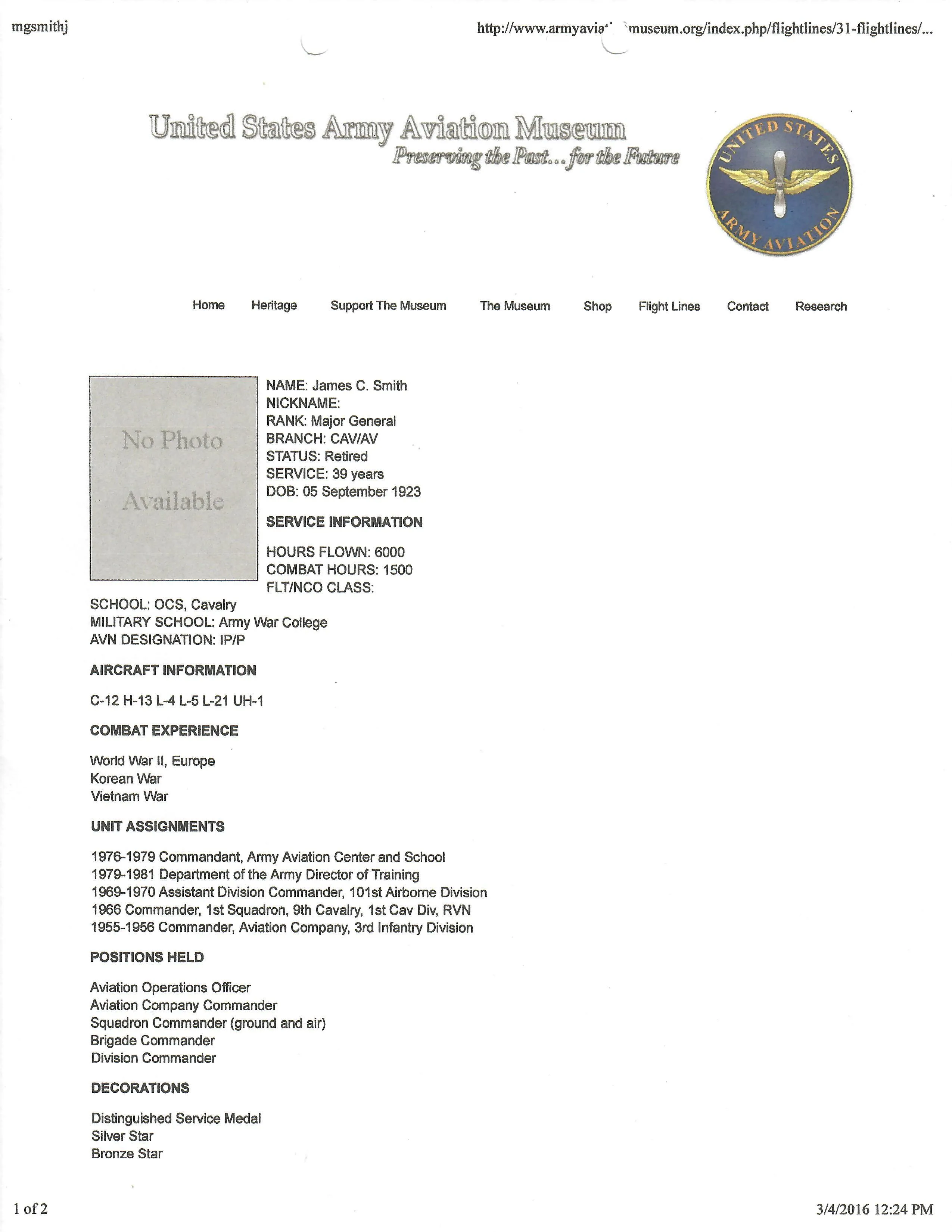

Original Item: Only One Available. Original Items: One-of-a-kind Set. The service of Major General James Clifton Smith is nicely summarized in his obituary (December, 2016) which can be read below and found at this .

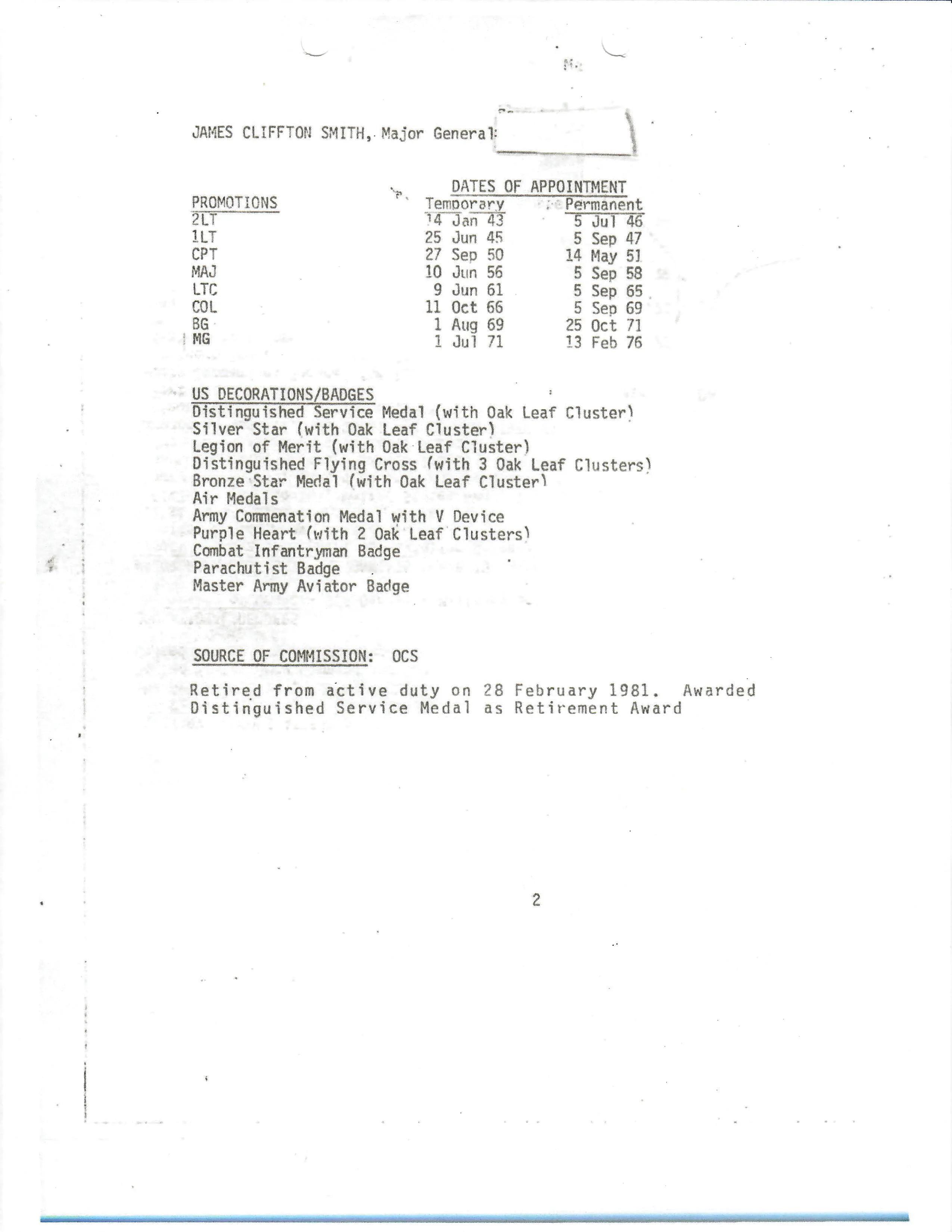

Army Maj. Gen. James Clifton Smith (Ret.) had a chest full of medals from his combat duty in three wars.

But in a 39-year military career, he was most proud of what he did to improve the safety of the troops: making training in instrument-flying standard for military pilots, advocating for night-vision goggles for fliers, and helping to develop the modern-day drone, a family member said.

“He was very pragmatic,” said R.J. Parsons, Smith’s nephew by marriage. “He could see the advantage of these types of things and what it meant to the airmen.”

Gen. James “Jim” Smith, a highly decorated veteran of three wars and father of seven, died Dec. 14 at his Lawrenceville residence. He was 93.

The path of Smith’s life was set in childhood. As a young boy, he would go with his father, a sergeant major in the acclaimed 6th Cavalry at Fort Oglethorpe in northwest Georgia, to visit and camp with the horse soldiers.

“It was said he essentially joined the Army when he was six,” daughter Heidi Smith said.

With his parents’ permission, Smith enlisted in the Army as a private at the tail end of World War II. He was 17.

A review board exempted him from basic training, deciding he already knew everything being taught to new soldiers, and he was immediately assigned to a platoon in Riley, Kansas.

He was shot several times by a sniper in Germany and nearly killed, his daughter said. His weight dropped to about 80 pounds, and he was told he wouldn’t see active duty again.

“He requested to create his own rehab program,” Heidi Smith said. “He was allowed to eat whatever he wanted from the mess hall and do whatever he needed to get fit again.” A review board soon deemed him “good to go.”

In nearly 40 years in the Army, Smith saw combat duty in World War II, the Korean Conflict and the Vietnam War, earning medals of valor including the Distinguished Service Medal and multiple Flying Crosses, Silver Stars and Purple Hearts.

When the Army took to the air, he was among the first young soldiers trained to fly. The late Eugene Patterson, who went on to become an award-winning and nationally known journalist, was with him at flight school training and remained a lifelong friend, his daughter said.

Gen. Smith is credited with major contributions in Vietnam and in later years to the Army’s advances in air mobility with helicopters.

In the early 1960s he was part of a task force of the U.S. Strike Command charged with analyzing the air mobility of the Air Force and Army.

As a field test officer specializing in tactical air reconnaissance, Smith was largely responsible for many of the organizational and training standards in aviation the Army and Air Force still employ.

The Army Aviation Association of America recognized Smith's contributions, naming him to the Army Aviation Hall of Fame in 1976 for his efforts in the 1960s.

Army Maj. Gen. Carl H. McNair Jr. (Ret.), said Smith always “gave the Army, his troops and his mission 200 percent, night and day. I often wondered when he slept,” McNair said.

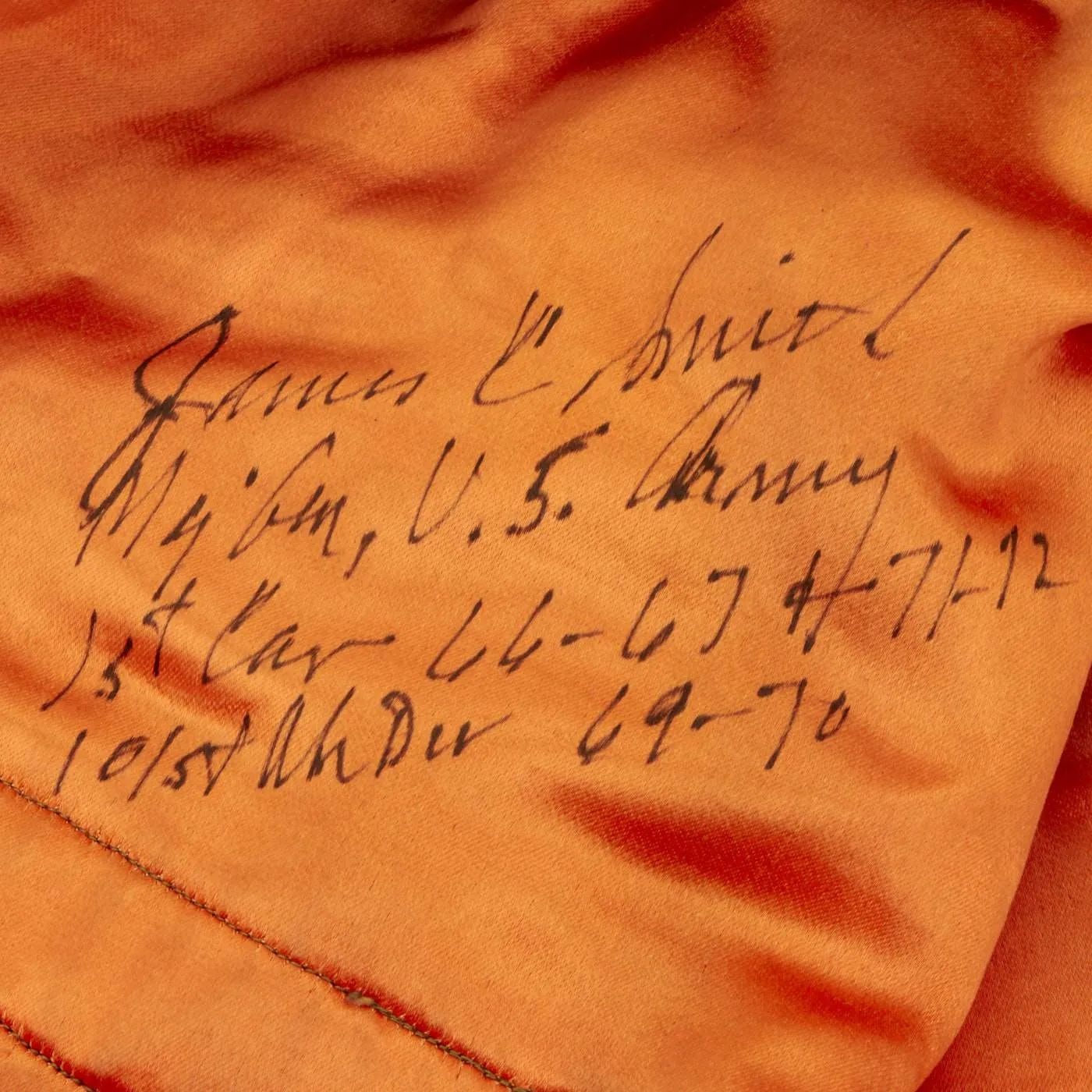

As deputy commanding general of the 1st Aviation Brigade, Gen. Smith’s call sign was “Hawk 5” and his nickname was “Hawk Eye.”

“He had an eye on everything as a commander must do in a combat theater and in the garrison preparing for combat,” said Gen. McNair, who was 10 years Smith’s junior and his friend for 50 years .”Thus, the nickname ‘Hawk Eye’ was very fitting, and we all learned from him.”

Smith showed his dedication and fortitude by going from one tough command to an even tougher one in Vietnam, remaining there as long as any commander, with the possible exceptions of Gen. William Westmoreland and Gen. Creighton Abrams, McNair said.

After retirement, Smith consulted with the Institute for Defense Analyses and assisted in the early development of unmanned aerial vehicles commonly known as drones, for battlefield reconnaissance and observation. He saw the drone as a potentially life-saving alternative to sending troops into danger zones, Parsons said.

Smith referred to Doris, his wife of 66 years, as the “gold standard” of military wives.

When he was stationed in Germany during the1960s, as the wall was being built between East and West Berlin, Doris traveled by troop transport plane to be with him. She stepped off the plane seven months pregnant with daughter Heidi and with five children 10 years old and younger at her side.

“That’s an Army wife,” Smith would say.

Heidi Smith said her dad was a “soldier’s soldier no matter what his rank.”

One of his traditions was to make Christmas Eve visits to the guard posts on base. He would bring a tape recorder, play Christmas music for the men on duty and talk to them about the families they had back home.

“He cared deeply about the well-being of his troops,” his daughter said. “Having grown up among soldiers, he could still relate to them. That was at the core of his leadership style.”

Gen. Smith is survived by his wife, Doris, seven children, 12 grandchildren and one great-grandchild.

Since his death, tributes have flowed in from soldiers who served under his command. A memorial service for Gen. Smith was held Dec. 17 in Snellville.

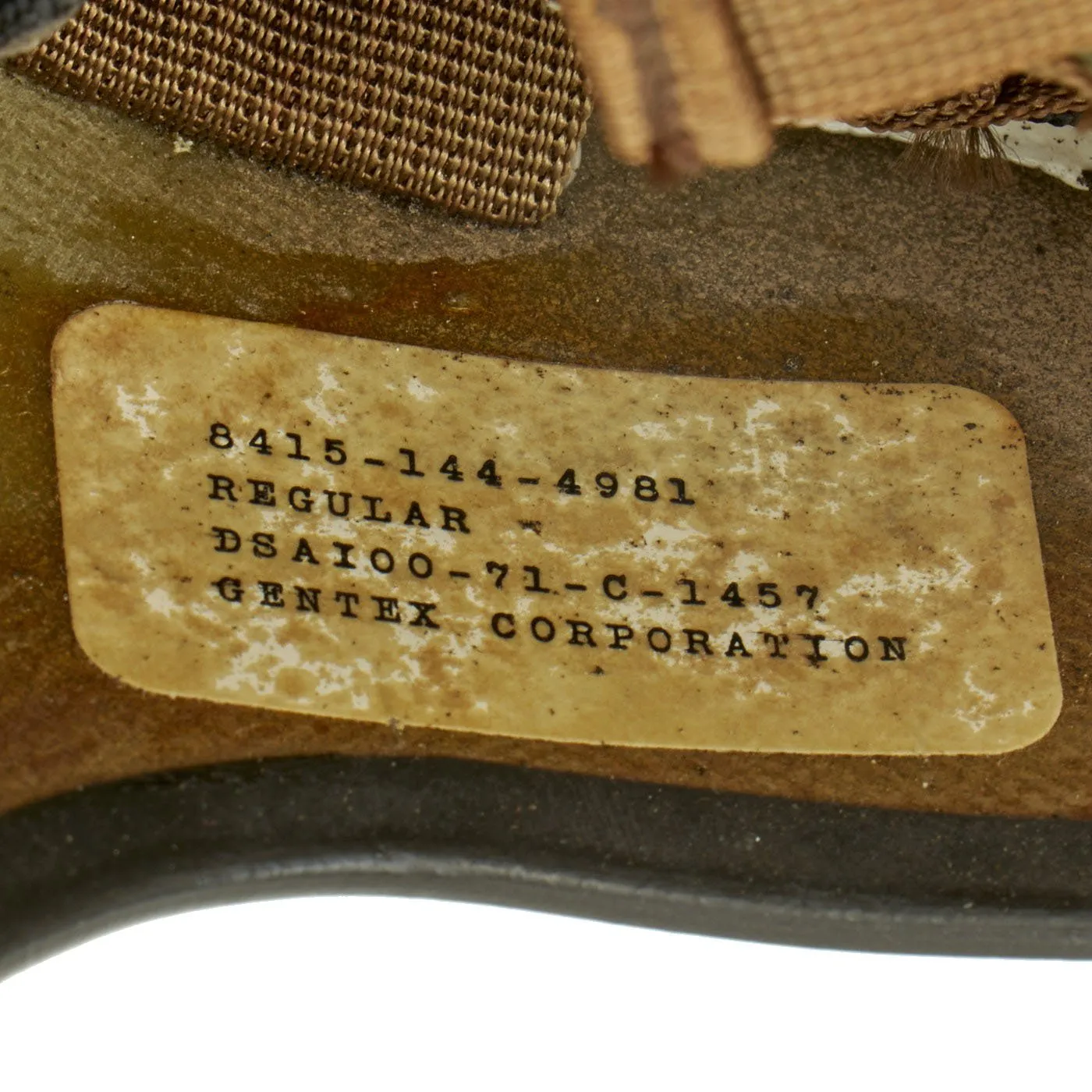

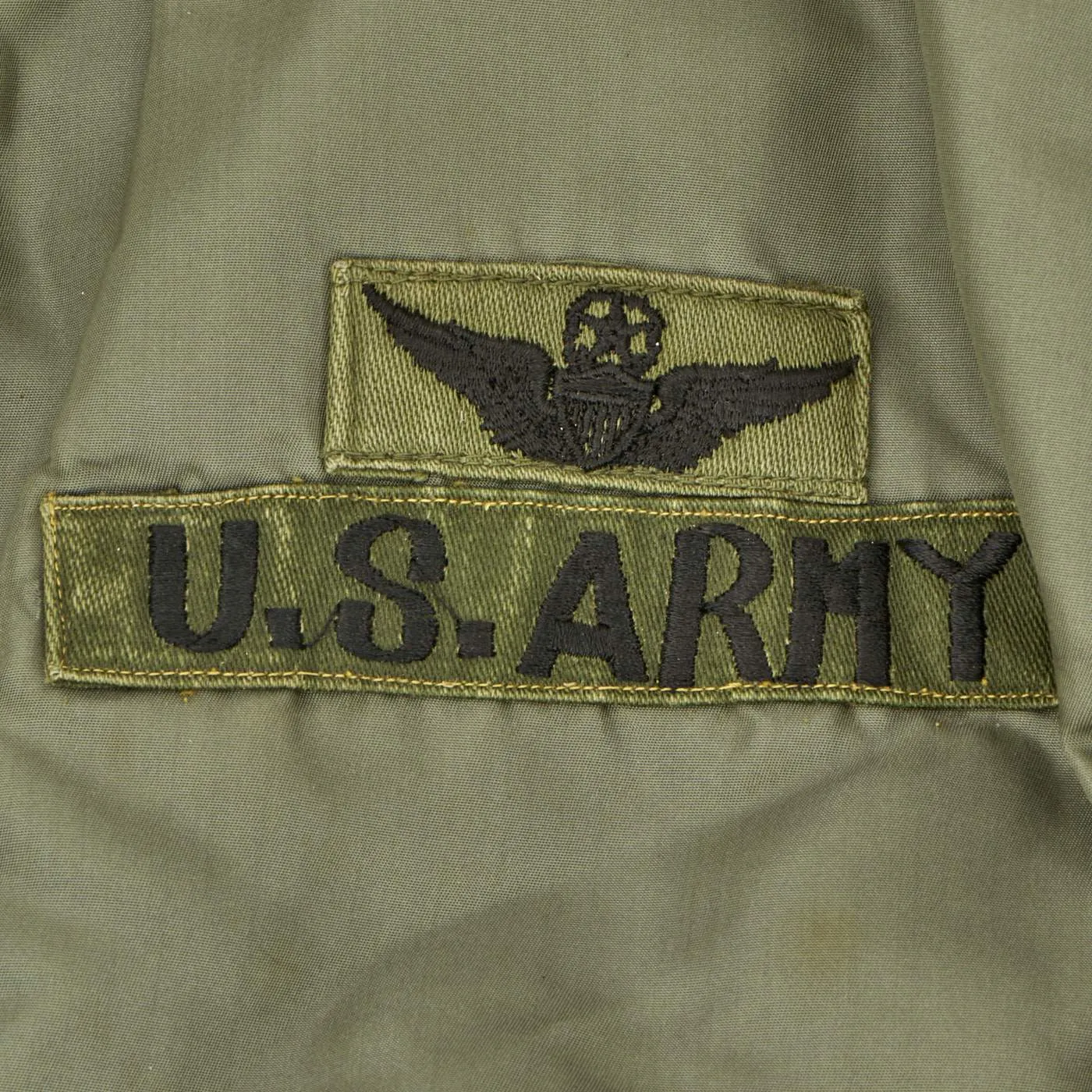

Included in this set are Major Gen Smith's Gentex SPH-4 Helicopter Pilot Helmet in size regular named to him on the reverse and his two star (Maj general) named MA1 Flying Jacket. Both pieces are offered in very good condition. Also included are photos copies of research and photos.

The Sound Protective Helmet-4 (SPH-4) is a derivative of the US Navy SPH-3 and was used by the US Army since 1970. The SPH-4 is a single-visor lighter-weight version of the SPH-3 and it replaced the two Army aircrew helmet then in use: The Navy-developed Aircrew Protective Helmet no 5 (APH-5) and the Army-developed Anti-fragmentation Helmet No. 1 (AFH-1). Both of these helmets were deficient in noise attenuation and retention capability. The SPH-4, which was specifically designed for sound protection, provided superior sound attenuation but the 1970 version provided no more impact protection than the APH-5A. As the sciences of crashworthiness and head injury prevention developed, it became evident that head injuries could be reduced by modifying the SPH-4.

Two types of head injury that might be prevented continued to occur after the introduction of the SPH-4. One was concussions severe enough to prevent the crewmember from saving himself from the crash site, and the other was skull fractures due to blows from the side (lateral). Furthermore, helmet retention proved to be a problem as well. A helmet can only protect a crewmember if it stays in place and it turned out that one in five crewmembers involved in severe crashes lost their helmet.

The original SPH-4 had a shell made of fibreglass cloth layers bonded by epoxy. The inner polystyrene foam energy absorbing liner was 97 mm (0.38") thick with a density of 5.2 lb/ft3. The helmet was fitted with a sling suspension liner and had a nape strap with a single snap on each side fitting to studs on a retention harness. The chin strap had a design strength of 150 lbs. The headset was mounted in 6 mm thick moulded plastic ear cups with excellent sound attenuation characteristics. A size regular helmet weighed 1.54 kg (3.4 lbs).

In 1974 the SPH-4 was modified with a thicker energy absorbing liner to reduce the risk of concussions. The new liner was 1.27 cm (0.50") thick and with the same density as the original liner. In 1982 the risk of concussions was reduced even further by manufacturing the energy absorbing liner with a lower density 4.5 lb/ft3. All in all the impact protection was improved about 33% over the original SPH-4 from 1970.

Nothing was done to the original SPH-4 design to reduce the risk of skull fractures due to blows from the side. The main culprit was the rigid plastic ear cups that turned out to be too strong in comparison with the skull around the ears. In case of a strong blow from the side the ear cup survived but the skull fractured. This problem was not addressed until the SPH-4B helmet was fielded.

Helmet retention, however, was improved. The original 1970 helmet had a chinstrap with single snap fasteners on each side and was designed to withstand a load of 150 lbs. In 1978 a double-Y chinstrap with two snap fasteners was incorporated to reduce failures. This chinstrap had a failure limit of 250 lbs based on the adjustment buckle strength. In 1980 a third chinstrap was introduced. It was fastened to the ear cup assembly on one side with a small screw and T-nut, and the other side with two snap fasteners. This chinstrap had a failure limit of 300 lbs but some failed at 280 lbs.